A Guide to Closed-End Funds

What Is a Closed-End Fund?

How do the Types of Closed-End Funds Differ?

Features of Closed-End Funds

Total Assets of Closed-End Funds

Sources of Closed-End Fund Information

Pricing for Traditional CEFs

Investment Return

Taxes

Regulation and Disclosure

Fees and Expenses

Buying and Selling Shares

Shareholder Information

For More Information

This guide includes an overview of the types of closed-end funds (CEFs) and how they operate. However, each CEF is different, and investors should learn more about a particular fund before investing. CEFs, like all investments, involve risk, including the possible loss of principal.

What Is a Closed-End Fund?

Closed-end funds (CEFs) are one of four main types of investment companies, along with mutual funds, exchange-traded funds (ETFs), and unit investment trusts (UITs). Historically, the vast majority of CEFs have been “listed” CEFs—investment companies that issue a fixed number of common shares in an initial public offering (IPO) that are publicly traded on an exchange or in the over-the-counter market, like traditional stocks. Once issued, shareholders may not redeem those shares directly to the fund (though some CEFs may repurchase shares through stock repurchase programs or through a tender for shares). Subsequent issuance of common shares generally only occurs through secondary or follow-on offerings, at-the-market offerings, rights offerings, or dividend reinvestments. Listed CEFs primarily include traditional CEFs but also include interval funds and business development companies (BDCs) that are listed on exchanges.

There are also “unlisted” CEFs, which have recently seen steady asset growth. Unlisted CEFs are not listed on an exchange but sold publicly to retail investors (mainly through intermediaries) or to certain qualified investors through private placement offerings. Unlike listed CEFs, unlisted CEFs do not issue a fixed number of shares but are permitted to continuously offer their shares at net asset value (NAV) following their IPO. As they are not traded on an exchange, unlisted CEFs engage in scheduled repurchases or tender offers for a certain percentage of the CEF’s shares to allow shareholders to exit the fund. The ability of a shareholder to exit the CEF is dependent on the timing of the scheduled repurchase or tender offer and whether the repurchase or tender is “over-subscribed.” Unlisted CEFs include interval funds, tender offer funds, and BDCs.

How do the Types of Closed-End Funds Differ?

There are four types of closed-end funds (CEFs): traditional funds, interval funds, tender offer funds, and business development companies (BDCs).

Traditional CEFs issue a fixed number of shares during an IPO that are then listed on an exchange or traded in the over-the-counter market where investors buy and sell them in the open market (i.e., all traditional CEFs are listed CEFs). The market price of a traditional CEF fluctuates like that of other publicly traded securities and is determined by supply and demand in the marketplace.

Interval funds, unlike traditional CEFs, are permitted to continuously offer their shares at NAV following their IPO. Most interval funds differ from traditional CEFs in that they do not offer liquidity via the secondary market (i.e., they typically are not listed on an exchange). Instead, they buy back shares by making periodic repurchase offers at NAV in compliance with Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) Rule 23c-3 under the 1940 Act. There are some interval funds, however, that are listed on an exchange and are bought and sold in the secondary market—and these funds continue to make periodic repurchases at NAV via Rule 23c-3. Certain unlisted interval funds are not available to the general public and are primarily held by qualified investors that meet income, wealth, and/or sizeable minimum investment thresholds. At year-end 2023, there were 92 interval funds with total assets of $77 billion.

For interval funds making continuous offerings, purchases resemble open-end mutual funds in that their shares typically are continuously offered and priced daily. However, unlike a mutual fund, shares are not continuously available for redemption but are repurchased by the fund at scheduled intervals (e.g., quarterly, semiannually, or annually). In 2023, 91 percent of interval funds had policies to repurchase shares every three months, while the remainder had policies to repurchase shares monthly, annually, or semi-annually. Further, the number of outstanding shares repurchased may vary but must be between 5 percent and 25 percent of outstanding shares. For more information on the different operational characteristics around interval fund repurchases, see Interval Funds: Operational Challenges and the Industry’s Way Forward.

Tender offer funds are generally unlisted and are permitted to continuously offer their shares at NAV. Like interval funds, certain tender offer funds are only sold to accredited investors or other types of qualified investors. Unlike interval funds, however, tender offer funds repurchase shares on a discretionary basis through a tender offer, which must comply with SEC Rule 13e-4 under the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 by filing a Schedule TO. There is no set schedule for when tender offer funds must conduct repurchases or how many shares they must tender. Some tender offer funds have held very few tender offers (e.g., once in the past 10 years), but most offer them more regularly (e.g., quarterly). In 2023, 50 percent of tender offer funds held tender offers four times during the year; 11 percent held between one and three tender offers; and the remaining 39 percent did not hold any tender offer during the year. At year-end 2023, there were 98 tender offer funds, with total assets of $60 billion.

BDCs differ from other CEFs in that they are not registered under the 1940 Act but instead elect to be subject to and regulated by certain provisions of the 1940 Act. BDCs primarily invest in small and medium-sized private companies, developing companies, and distressed companies that do not otherwise have access to lending. In particular, BDCs must invest at least 70 percent of their assets in domestic private companies or domestic public companies that have market capitalizations of $250 million or less. At year-end 2023, there were 132 BDCs with total net assets of $159 billion.

BDCs may be listed or unlisted. Listed BDCs are bought and sold on stock exchanges in the secondary market. Unlisted BDCs may either be non-traded or private. Non-traded BDCs are continuously offered (like unlisted interval funds and tender offer funds), may be available to retail investors, and often conduct periodic repurchase offers for investors to redeem their shares. Private BDCs are sold through private placement offerings only to qualified investors. Private BDCs typically only offer those investors the chance to liquidate their shares by either going public (e.g., holding an IPO) or choosing to unwind the portfolio and liquidate the fund. These liquidity events often occur between five and ten years following the initial private placement.

Features of Closed-End Funds

A CEF’s assets are professionally managed in accordance with the fund’s investment objectives and policies and may be invested in stocks, bonds, and other assets. Because CEFs do not face daily redemptions, there is little need to maintain cash reserves and they can typically be fully invested according to their strategies. Also, other than for any upcoming repurchase or tender offer, CEFs do not sell portfolio securities daily and have the flexibility to invest in less-liquid portfolio securities. For example, a CEF may invest in securities of very small companies, municipal bonds that are not widely traded, or securities traded in countries that do not have fully developed securities markets.

CEFs also are permitted to issue one class of preferred shares in addition to common shares. Holders of preferred shares are paid dividends but do not participate in the gains and losses on the fund’s investments. Issuing preferred shares allows a CEF to raise additional capital, which it can use to purchase more assets for its portfolio.

CEFs have the ability, subject to strict regulatory limits, to use leverage as part of their investment strategy. The use of leverage by a CEF can allow it to achieve higher long-term returns but also increases risk and the likelihood of share price volatility.

Total Assets of Closed-End Funds

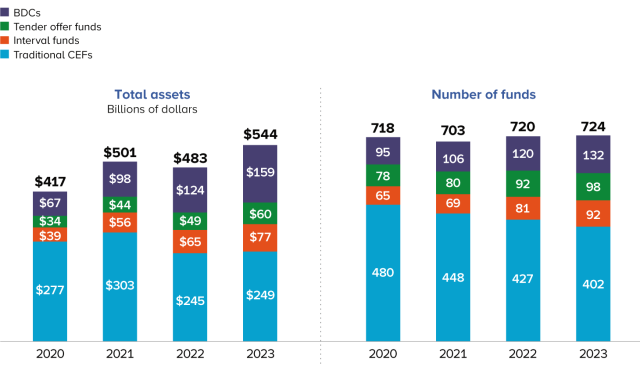

As of year-end 2023, there were 724 CEFs, with $544 billion in total assets—402 traditional CEFs, with $249 billion in total assets; 92 interval funds, with $77 billion in total assets; 98 tender offer funds, with $60 billion in total assets; and 132 BDCs, with $159 billion in total net assets.

Waning Presence of Traditional CEFs Is Offset by Growth of Interval Funds, Tender Offer Funds, and BDCs

Year-end

Note: Data are based on quarterly public filings between November and January. Data for BDCs are total net assets.

Sources: Investment Company Institute and publicly vailable SECform N-PORT, N-CEN, 10-Q, and 10-K filings.

At year-end 2023, bond CEFs accounted for the majority of assets (60 percent) in traditional CEFs, with the remainder held by equity CEFs.

Bond CEFs are subject to some degree of market risk and credit risk. Market risk is the risk that interest rates will rise, lowering the value of bonds held in the fund’s portfolio. Generally speaking, the longer the remaining maturity of a fund’s portfolio securities, the greater the volatility of its net asset value (NAV) due to market risk. Credit risk is the risk that issuers of bonds held by the fund will default on their promise to pay principal and interest. A bond CEF’s investment policies typically define the credit quality and maturity of the investments the fund may make.

Equity CEFs are subject to the risk that the portfolio securities held by the fund will decline in value, thus causing a decline in the fund’s NAV and market price (if it’s a listed CEF). The value of a particular stock in a fund’s portfolio may increase or decrease for a variety of reasons, including the business activities and financial condition of the issuer of the stock, market and economic conditions affecting the issuer’s business, or the stock market generally.

>Sources of Closed-End Fund Information

Information on traditional CEFs, including NAVs, market prices, and discounts or premiums, can be found in stock market tables on most major financial websites. Some stock market tables offer other information, including a CEF’s high and low market prices for the past 52 weeks; distributions paid to shareholders during the past 12 months; and the high, low, and closing market prices for the previous day.

Other sources of information about CEFs include the financial press and the fund sponsor. Many CEF sponsors have personnel available to answer questions about the fund and to provide written information. In addition, periodic reports, proxy statements, and (in some cases) fund registration statements can be found on the website of the US Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) at www.sec.gov.

Pricing for Traditional CEFs

More than 95 percent of traditional CEFs calculate the value of their portfolios every business day, while the rest calculate their portfolio values weekly or on some other basis. The NAV of a CEF is calculated by subtracting the fund’s liabilities (e.g., fund borrowing) from the current market value of its assets and dividing by the total number of shares outstanding. The NAV changes as the total value of the underlying portfolio securities rises or falls or the fund’s liabilities change.

Because a traditional CEF’s shares trade based on investor demand, the fund may trade at a price higher or lower than its NAV. A CEF trading at a share price higher than its NAV is said to be trading at a “premium” to the NAV, while a CEF trading at a share price lower than its NAV is said to be trading at a “discount.” Funds may trade at premiums or discounts to the NAV for a number of potential reasons, such as market perceptions or investor sentiment. For example, a CEF that invests in securities that are anticipated to generate above-average future returns and are difficult for retail investors to obtain directly may trade at a premium because of a high level of market interest. By contrast, a CEF with large unrealized capital gains may trade at a discount because investors will have priced in any perceived tax liability. Unlisted CEFs—which are sold and repurchased based on NAV—do not have premiums or discounts.

Fund management may take measures in an attempt to reduce discounts, including increasing market visibility of the fund through public reports and communications. A CEF also may attempt to increase the demand for its shares by offering a dividend reinvestment plan, engaging in tender offers (the fund offers to purchase its shares directly from shareholders at or close to NAV), or instituting a stock purchase program (the fund purchases its shares on the open market). Further, some CEFs periodically may consider converting to either an open-end fund or an exchange-traded fund, which would permit shareholders to redeem their shares at NAV.

Of course, any such measures must be approved by the fund’s board of directors as consistent with the best interests of the fund.

Investment Return

For listed CEFs, the fund’s investment return has two primary components:

- Share price appreciation or depreciation: A listed CEF’s share price may increase or decrease based on market perceptions about the types of securities or geographic region in which the fund invests and perceptions about the fund or its investment manager.

- Distributions: A CEF makes up to three types of distributions to shareholders: ordinary dividends, capital gains, and return of capital. Some CEFs follow a managed distribution policy, which allows them to provide predictable, but not guaranteed, cash flow to common shareholders. The payment from a fund pursuant to a managed distribution policy is typically paid to common shareholders on a monthly or quarterly basis. Managed distribution policies are used most often in multi-strategy or equity-based CEFs.

- Ordinary dividends: A CEF earns interest and dividend income from securities held in its portfolio. This income, minus fund operating costs, typically is paid to shareholders as ordinary dividend distributions.

- Capital gains: If a fund profits from selling securities during a calendar year, the fund may distribute the gains to investors. Distributions of capital gains typically occur annually near the end of the calendar year. Some funds, particularly those with managed distribution plans, distribute capital gains more frequently.

- Return of capital: A CEF may return capital back to shareholders. Return of capital may occur in a variety of circumstances, including when a fund is acting as a pass-through. In that circumstance, one or more of its underlying holdings had a return of capital (usually true for master limited partnerships) and the CEF is merely passing this payment through to its shareholders. In other circumstances, a CEF with a managed distribution policy may return capital to maintain a stable regular distribution that, over the long term, matches the fund’s distributions to its total return.

Taxes

In order to avoid the imposition of federal tax at the fund level, a CEF must meet Internal Revenue Service (IRS) requirements for sources of income and diversification of portfolio holdings and must distribute substantially all of its income and capital gains to shareholders annually.

Generally, shareholders of CEFs must pay income taxes on the income and capital gains distributed to them. Each CEF will provide an IRS Form 1099 to its shareholders annually that summarizes the fund’s distributions. When a shareholder sells shares of a CEF, the shareholder may realize either a taxable gain or a loss.

Regulation and Disclosure

CEFs are regulated under federal laws designed to protect investors. The Investment Company Act of 1940 requires all funds to register with the SEC to meet certain operating standards and to deliver information to investors; the Securities Act of 1933 requires registration of the fund’s shares and the delivery of a prospectus to investors who purchase shares in the IPO; and the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 regulates the secondary market trading of the fund’s shares and establishes antifraud standards governing such trading. Finally, the Investment Advisers Act of 1940 regulates the conduct of fund investment managers and requires them to register with the SEC.

All US-registered CEFs are subject to stringent laws and oversight by the SEC and the exchanges on which their shares are listed. All funds must provide a written prospectus containing complete disclosure about the fund when its shares are initially offered to the public. Following the IPO, other disclosure documents, including the annual and semiannual reports and the proxy statement, provide information to investors.

The SEC conducts inspections of fund operations to determine compliance with applicable laws and SEC regulations. Stock exchanges on which a fund’s shares are listed also impose certain requirements. Stock exchanges require the prompt public disclosure of material information and require certain corporate governance and management procedures, including annual shareholder meetings.

Fees and Expenses

A CEF incurs operating expenses, including those associated with fund portfolio management, fund business operations, custody of the fund’s assets, and shareholder services. These operating expenses are paid by the fund from its assets before any distributions are made to investors. A fund’s expenses are summarized in a fee table included in the fund’s prospectus. Updated expense information is provided in a fund’s semiannual and annual reports to shareholders.

Buying and Selling Shares

Listed CEF shares are bought and sold in the same way one would buy corporate stocks—through registered broker-dealers. During the IPO, a fixed number of CEF shares are offered to investors. After the IPO, an investor may purchase shares of existing CEFs in the secondary market.

In an IPO, a CEF’s shares typically are sold subject to a sales charge that is paid to the underwriter and the broker-dealer who sells the shares. A CEF investor buying or selling shares in the secondary market likely will pay a sales commission to a broker at the time of the transaction. The purchase or sale price for shares reflects the current market price, adjusted for the brokerage commission.

Shareholder Information

The annual and semiannual reports that CEFs provide to shareholders contain financial statements and information on the fund’s portfolio, performance, and investment goals and policies. A fund’s annual report contains financial statements that have been audited by the fund’s independent public accountants and management’s discussion of fund operations, investment results, and strategies. In addition, a fund or an investor’s broker may provide statements that update and summarize individual account holdings and values.

For More Information

- “The Closed-End Fund Market, 2023,” ICI Research Perspective

- Frequently Asked Questions About Closed-End Funds and Their Use of Leverage

- Find quarterly updates to closed-end fund asset data at www.ici.org/research/stats/closedend.

May 2024